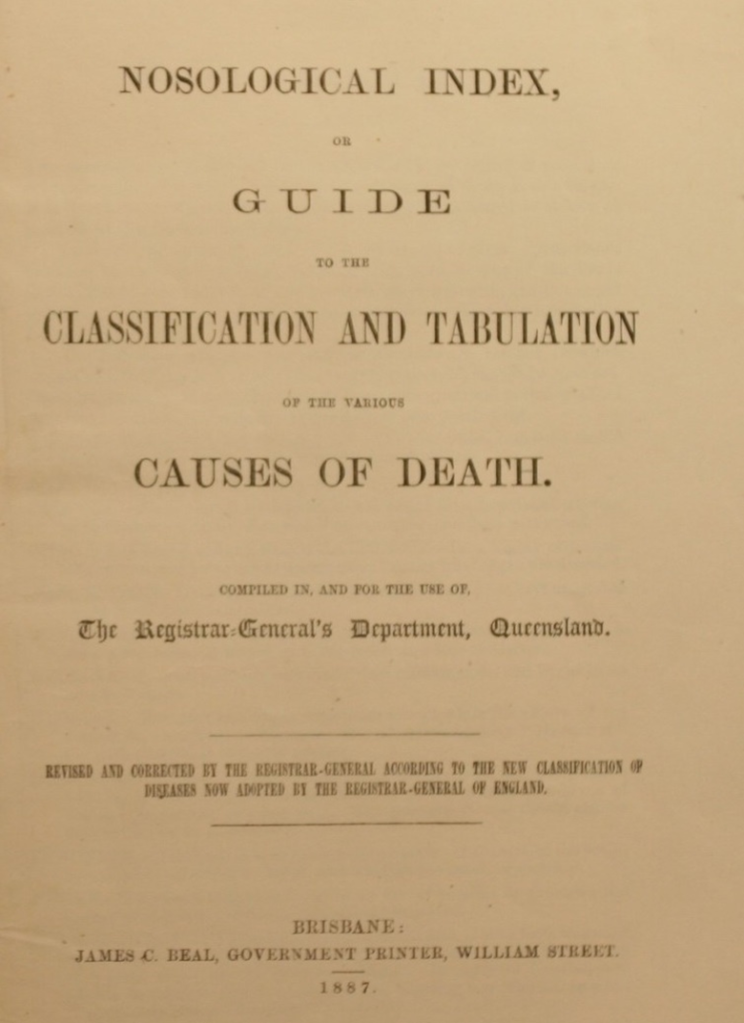

By the mid-1880s, the Queensland Registrar-General of Births, Deaths and Marriages was becoming increasingly frustrated by non-medical, vague and fanciful causes of death submitted by the district registrars. Although this may have been expected when the death was notified by a general member of the public, a number of these causes were submitted by coroners and even medical practitioners. In addition, reporting inconsistency between registration districts made it difficult to compile meaningful mortality statistics.1 In response, the Nosological Index or Guide to the Classification and Tabulation of the various Causes of Death was introduced in 1887 which cross-referenced common terminology with medical nomenclature. It was distributed to all district and hospital registrars for implementation.2

The cause of 950 Chinese deaths between 1857 and 1900 was assembled from death registrations, cemetery records and coroners’ reports in the compilation the Queensland Chinese Death Index. By reclassifying these causes with the Nosological Index, it is possible to compile mortality tables for geographical areas, occupations and specific time periods.

The 43-page Nosological Index grouped causes of death into eight broad categories.

| Class | Top-level Description |

| I | Zymotic (contagious) diseases |

| II | Parasitic diseases |

| III | Dietetic diseases |

| IV | Constitutional diseases |

| V | Developmental diseases |

| VI | Local diseases |

| VII | Violence / accident / negligence |

| VIII | Ill-defined and not specified causes |

Contrary to the macabre reportage in the contemporary newspapers, the Chinese were far more likely to die falling off horses than by being eaten by crocodiles. Shepherds had the highest number of mishaps with horses, while market gardeners died more frequently of snake bite. They were more likely to be murdered by their countryman than by any other group.3 Death by opium whether by an accidental or deliberate overdose or by chronic use was constant over the period but never exceeded 3% of registered deaths. The Registrar General also directed that if a cause of death could be either accidental or suicidal, the local registrar was to make further enquiries to ascertain the circumstances of the death and accordingly classify them. Suicide in the Queensland colonial Chinese population was discussed in a previous post, The Grim Reality.

| Cause | Nosology Code | Number (%) |

| Drowning | VII.01.09 – Accidental | 25 (2.6) |

| VII.03.04 – Suicidal | 3 (0.3) | |

| Opium overdose | VII.01.07 – Accidental | 20 (2.1) |

| VII.03.03 – Suicidal | 4 (0.4) | |

| Suicide | VII.03.06 – Hanging / strangulation | 24 (2.5) |

| VII.03.02 – Stabs / cuts / wounds | 8 (0.8) | |

| Murdered | VII.02.01a – by Whites | 9 (0.9) |

| VII.02.01b – by Coloureds (including Chinese – 9) | 12 (1.2) | |

| VII.02.01c – by Aboriginals | 4 (0.4) |

Death by disease was more prevalent for the period up to 1900. After then, death by age-related causes and senility takes precedence. Tuberculosis claimed its victims at the average age of 44 years. The five deaths attributed to the bubonic plague all occurred in 1900.

| Class | Nosology Code | Number (%) |

| Constitutional | IV.01.06 – Phthisis / Tuberculosis | 66 (6.9) |

| Zymotic | I.01.13 – Fever (not defined) | 47 (4.7) |

| Ill-defined | VIII.01.02 – Debility | 24 (2.5) |

| Zymotic | I.02.03 – Dysentery | 18 (1.9) |

| Zymotic | I.01.06a – Typhoid | 17 (1.7) |

| Local | VI.03.01 – Heart disease | 16 (1.6) |

| Zymotic | I.01.15 – Leprosy | 6 (0.6) |

| Zymotic | I.01.06a – Bubonic plague | 5 (0.5) |

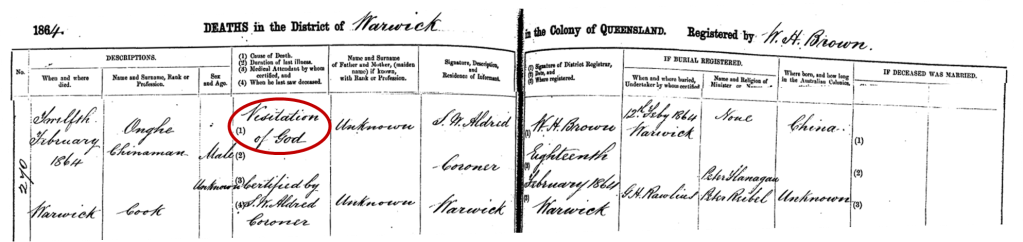

According to the Nosological Index, a Visitation of God was a term that should be avoided when a more definite one could be given.4 When the cause of death could not be specified, it was classified as VIII.1.12.

References

1. QSA ITM847252 1887/8208. A copy of the Nosological Index is incorporated in this batch of Colonial Secretary’s Office letters.

2. Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton) 11 June 1887:6

3. Queenslander 5 December 1885:889

4. Nosological Index (1887) 4